In 2021, my employer docked my pay and threatened to fire me, because I defied their Covid vaccine mandate. Confronted with financial hardship, I sold my house in Ontario, and moved my family to the province of Saskatchewan in western Canada, thinking that the prairies offered more freedom.

I was wrong.

In the mid-sized Ontario town I left, I could frolic from shop to church to rink without wearing a mask or showing my vaccine card. Despite there being medical mandates on paper, the local police were not keen on upholding lockdown tyranny, deeming it below them. The local businessmen grew wary of checking vaccine QR codes. My neighbourhood was dotted with signs reading “No More Lockdowns” and the like.

Saskatchewan, by contrast, was a grim nightmare. Although there are sensible, freedom-loving folks in the prairies, their voices are drowned by paranoid boomers whose cacklings are woven into law. I met a shopkeeper from Nipawin, a town of 4,000, whose neighbours rang the cops on her for hosting a small outdoor party. The City of Saskatoon deployed surveillance drones to ensure that residents were social distancing. When I stepped into shops without a mask, as was my habit, I was harassed by security guards and low-level employees. My friend was fined $2,800 for joining an outdoor protest.

Then, I started to notice something: Saskatchewan is wired for rigid conformity. For example, Saskatoon has speed and traffic cameras on every highway. In Ontario, on the other hand, speed cameras are set up and then quickly destroyed by vigilantes. There is something paradoxical about the typical prairie Canadian: their image is one of liberty, cowboys, and wild winters, but in truth, they are blindly obedient to authority.

This makes sense to some degree: settling the prairies in the 19th and early 20th centuries was tough, and the Canadian government provided much-needed help to pioneers. Institutions like The North-West Mounted Police and public schools raised trust in government, and so did the building of the Canadian Pacific Railway. It is no surprise that men who tried to farm amidst harsh winters would cling to stable public establishments.

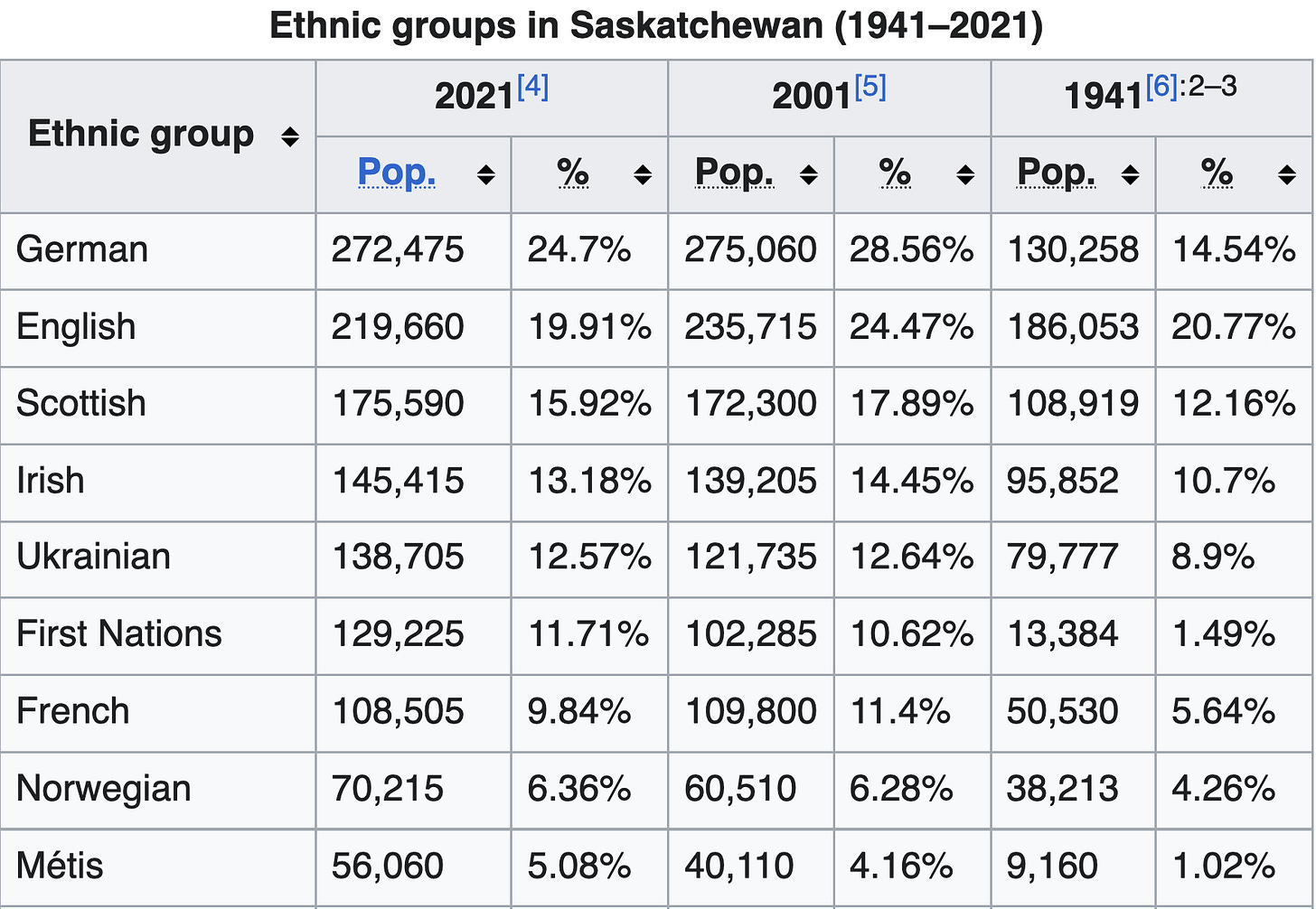

Yet, I wonder if Saskatchewan’s ethnic makeup explains, in part, its prairie character. The province is one-quarter German, one-tenth Ukrainian, and one-tenth indigenous. These are populations with no long history of democracy, nor any concept of rights. Germany has reared strongmen like Frederick the Great, Otto von Bismarck, and Adolf Hitler. The land now known as Ukraine has been through communism, imperialism, and monarchy. The Plains Indians of Canada — the Cree, the Dene, the Saulteaux, etc. — chose their chiefs based on skill and courage in battle, not via the popular vote.

One might expect that, over a hundred or so years, Germans, Ukrainians, and Plains Indians would adopt the precepts of British parliamentary democracy which Canada is founded upon. Yet, if Garret Jones’s book, The Culture Transplant: How Migrants Make The Economies They Move To A Lot Like The Ones They Left, is correct, then we should instead expect small-town Saskatchewan — home to fewer British and Dutch — to be more authoritarian than small-town Ontario, where these groups predominate. Furthermore, we should expect this dynamic to persist for decades.

Jones’s book is excellent, though its conclusions are somewhat obvious in hindsight. The message is simple: culture is the most important driver of economic growth. A million Englishmen moving to Minnesota is better for that state’s economy than a million migrants from Somalia. This is not just because Somalis are low-skilled; rather, it is because Somali culture contains traits which weaken economic growth, such as lower trust, political corruption, and a tendency towards violent conflict. Furthermore, culture is a slow-changing trait; it is unlikely that Somali immigrants, even up to the fourth generation, will ever completely assimilate.

That is not what Jones says explicitly, of course, — this book was published by Stanford University Press, after all, and Jones, a professor of economics at George Mason University, needs to maintain his stellar reputation — but that is the clear implication. As he summarizes in the last chapter,

If the the next hundred years is at all like the last hundred — or the last five hundred — we can predict that year after year of massive immigration from the world’s poorest countries into the I-7, the world’s most innovative nations, would eventually tend to have effects like these:

The quality of government would fall; corruption would rise.

Social conflict would increase — and so would the risk of civil war.

Trust — and probably trustworthiness — toward strangers would decline.

Support would rise for higher minimum wages and laws making it harder to fire workers.

Innovation would decline overall, and since new innovations eventually spread across the entire planet, the entire planet would eventually lose out.

These omens are troubling, especially now that Western countries are experimenting with mass immigration from The Third World.

In other words, people matter for prosperity, not places. Canada is not wealthy because of its magical soil, but rather because it was settled by Europeans, whose culture is conducive to economic growth. This is plain to anyone with eyes and half-a-brain, but Jones gives academic credence to this observation by citing peer-reviewed studies in economics and political science, as well as suggesting mechanisms through which migrants transfer growth-promoting culture to regions they settle.

Much is made of the role of technology, a key driver of economic development. Jones cites a seminal study which quantifies technological progress in five sectors: agriculture, transportation, military, industry, and communications. The study shows that if a migrant’s ancestors are exposed to advanced technology in the year 1500, then this does a superb job of predicting higher incomes today. Although the U.S., as a physical location, has had weak historical exposure to technology, it was nevertheless settled by migrants whose European ancestors oversaw the development of the printing press, spinning wheels, eyeglasses, cannons, etc. In essence, America’s wealth stems from being settled by those with experience of using advanced technology.

Jones quickly dismisses objections that this result is driven by geography, colonialism, or institutions. When these explanations are proffered as alternatives, migration-adjusted technology in 1500 always trumps them. Demographics is destiny. As the author writes,

Over the last five centuries, for the world as a whole, it’s fair to summarize economic history in this way: the more things change, the more they stay the same — but only when you adjust for migration.

Immigration determines the economic fate of countries, but it can also spark violence. Jones writes that, “when ethnically diverse groups disagree with each other on cultural issues, the chance of violence rises.” If Bengalis and Sicilians become neighbours, then expect fisticuffs. By contrast, Europeans, who have a broadly similar culture, are unaffected by European ethnic diversity — it generally does not matter if Frenchmen live beside Germans, or if Poles farm alongside Ukrainians.

(Granted, Europeans have fought wars of religion among themselves, but this confirms the point about shared values.)

If shared values do not exist, then ethnic diversity is just bad. Jones documents with precision how ethnic diversity within companies reduces profitability, how diversity is associated with worse public goods provision, and how it leads to corrupt political institutions. There is one exception to this: weak evidence that ethnic diversity in corporate boards improves company performance, which Jones chalks up to hiring from a broader, more talented pool of outsiders. Yet, in study after study, there is no benefit to diversity per se.

If it were possible to assimilate immigrants into a growth-promoting culture, then everyone could live peacefully and profitably in a multi-ethnic democracy. However, when Jones examines this question using survey data, he arrives at a troubling conclusion: assimilation is a myth. Fourth-generation immigrants to the U.S. maintain similar attitudes as their fresh-off-the-boat ancestors:

By the fourth generation, after scores of years in America, have immigrants finally assimilated? Or have they at least, say, 90 percent assimilated? Nope.

In particular, he notes that political attitudes between old-stock Americans and newcomers do not converge. The U.S., with its love of liberty and guns, cannot continue, in a traditional sense, when faced with boatloads of immigrant invaders.

The Culture Transplant is worth reading, especially since Jones successfully makes complex economics papers understandable to laymen. He is so confident that migration matters that he even offers a solution to under-development in Southeast Asia: encourage Chinese people to move to The Philippines, Burma, and other impoverished nations. When the Chinese settled in Singapore and Taiwan, after all, those countries became extraordinarily rich.

There is, of course, a dark side of all this. My immediate concern is what Jones’s findings portend for Canada, which has faced record immigration in recent years, causing its population to grow by 3 percent per year. Most of these immigrants, whom I shall henceforth call “invaders,” are from poor countries: India, The Philippines, Nigeria, etc. If Jones is correct, then we should expect that Canada will converge to Third World levels of poverty, filth, and corruption.

In some ways, this is already happening. Canada’s per-capita income growth has been stagnant over the past decade, and political corruption is rising. If you drive through Brampton, Ontario, which is mostly Indian, then you’ll notice the crumbling infrastructure, garbage tossed into the streets, and rude drivers. In other words, Brampton is turning into India, and so is the rest of Canada, albeit at a slower pace.

I do not wish to be overly pessimistic. Canada, despite its flaws, will continue to retain European-origin peoples. I suspect that it will turn into a version of Argentina, the decline of which Jones describes admirably in The Culture Transplant:

The migrants, or at least a large, politically organized subset of them, bring ideas from their homelands, ideas that weren’t selling back there. Socialism, anarchism, strong labor unions, strands of Marxism — they import these ideas and more to their new home, ideas that were barely on the map beforehand…

And because this land is a democracy, more or less, the politicians respond to the voters. First in baby steps, but that isn’t enough to please the migrant activists and those who have converted to the cause. And as the activists push harder for socialism, the elites start to push back, even trying to draw in the military to stand on the side of tradition. But military leaders are divided — some think that the socialist activists make a lot of good points…

…[The socialists] promise lots of good-paying government jobs, jobs with stability, and that has a lot of appeal. And the socialists promise a strong safety net as well — a source of comfort to an ever-anxious middle class afraid that job loss or illness could mean a permanent move to poverty.

…Ultimately, a fusionist leader rises to power — blending the substance of the Left with some of the trappings of the Right. He pushes for high taxes on elites, he increases government regulation over the economy, and he pushes for higher government spending. His wife becomes famous in her own right, creating charitable organizations that are the beginnings of a welfare state.

This is what happened to Argentina, after it faced hoards of Italian migrants, resulting in the election of Juan Peron. The result was decades of stagnant wages and frequent financial crises. Canada will likely suffer a similar fate, being confined to the status of a second-world country not unlike Brazil. To be sure, there are a good portion of East Asians within Canada, mostly from China, but not enough to offset the balance of Indian, Filipino, and African invaders. The future is bleak.

The solution to all of this, of course, is mass deportations — and that is the moderate policy, before violence becomes widespread of its own making. As Jones shows, ethnic and cultural diversity lead to violence. I would not be surprised if, in the coming years, white Canadians were to discover their ethnic conscience, and engage in targeted attacks against the Indian invaders. Mass deportations is simply the humane solution to prevent this outcome.

However, Canada’s economic elite won’t allow deportations, because they benefit from the current state of affairs. Canadian industry has always been heavily concentrated, run by oligopolies in technology, banking, and retail; The “Big Five” Canadian banks control 85 percent of the country’s financial sector, for instance. Canadians have tolerated high cellphone costs, banking fees, and grocery prices — as long as workers were afforded well-paying jobs. That social contract has been ripped apart by immigration policy, subsidizing invaders to come in and grab jobs at below-market wages. No politician will allow that to reverse.

And so, we are stuck in a rut. Canada’s best hope is that the U.S., covertly or overtly, interferes in its political process, up to and including Apache helicopters circling Ottawa — a scenario

spells out in his brilliant essay, “Maple Maidan,” which should be required reading for every educated Canuck. Although it is not ideal, a right-wing and competent White House can break Canada’s political malaise, and usher in a new era of prosperity, free from The Third World marauders. Perhaps this is a pipe dream, but it is more realistic than hoping that Canada can save itself.

Very interesting article.

As someone who lived in South Korea for 15 years and loved the culture of the region I gotta say that East Asians (especially Koreans, Japanese and Taiwanese) are great immigrants. Ditto for many Southeast Asians as we see the rise of Malaysia and Singapore.

But regardless to where the immigrants come from large numbers are definitely not conducive to assimilation. Many new immigrants can be like the European colonialists of the past and primarily hang out within their own groups.

I am sure I am not unique as a Canadian in going from being a supporter of immigration to hating mass migration.

This article is excellent. I’ll share some thoughts in detail when I get the time, but for now, as a fellow unvaccinated Canadian that had people wanting to fight me for not wearing a mask, this spoke to me.