The Dark Origins of The Federal Reserve (Part 1): Economic Alchemy

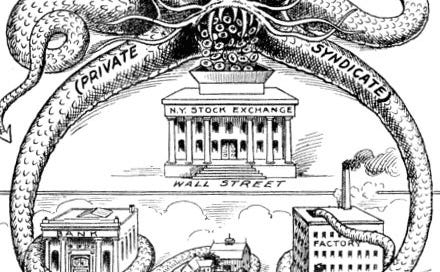

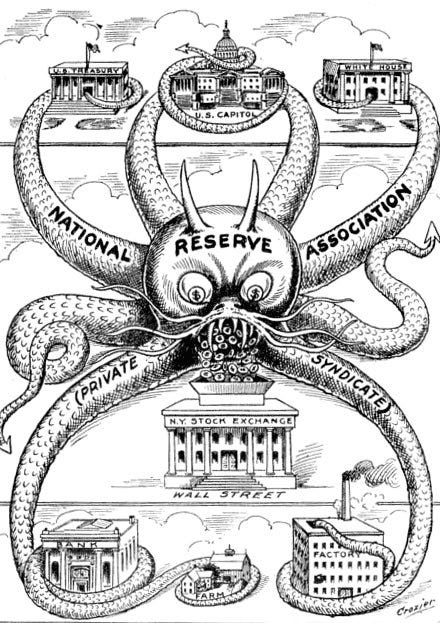

Conceived in secret, a wicked enterprise

“There is no subtler, no surer means of overturning the existing basis of society than to debauch the currency. The process engages all the hidden forces of economic law on the side of destruction, and does it in a manner which not one man in a million is able to diagnose.”

-John Maynard Keynes.

Financial jargon confuses people. When words like credit default swap or Federal Funds Rate flash across the screen, most viewers tune out. Of course, there is a certain level of knowledge required to be fluent in economics, but the basic concepts are simple. The problem is that if regular folk understood how the financial system truly works, then there would be riots and beheadings.

The key to revealing these mysteries is to understand what money is, and who controls it. What money is seems obvious: anything used as a medium of exchange, such as gold, cash, silver, etc. Who controls money is less clear, but it matters, because these schemers enrich themselves at the expense of others. The Federal Reserve, the United States’s central bank, is one of those controllers of the currency, and has used its influence throughout time to the benefit of Wall Street, at the expense of Main Street.

Because it requires some basic economics background, I have broken up this history of the Federal Reserve into two (possibly three) parts. Part One here deals with what money is, and who controls it. If you feel that you are sufficiently well-versed in economics, then you can skip this part and read Part Two.

And, of course, please consider subscribing.

What is money?

In general, money is a medium of exchange: in other words, anything used to purchase goods and services. Historically, gold and silver were widely used as money due to their malleability and beauty, as well as the fact that they’re hard to mimic or create, and almost impossible to destroy. Gold and silver have another advantage: it is difficult to mine them, thus limiting the quantity. These factors ensure that gold and silver money retain their value over time, making them ideal forms of money.

Compare that to fiat money, which lacks intrinsic value and can be easily eroded by making it more available. An example is paper cash. The government can always print more cash, debauching its worth. Gold and silver, on the other hand, cannot be ‘printed’ overnight, preventing them from losing value. All currencies today, such as the U.S. dollar or Euro, are fiat currencies, which explains why their value has gone down over time: after all, it takes more dollars to purchase gasoline in 2022 than it did in 2002.

NOTE: Inflation means a general rise in prices.

Gold as Money

Fiat money is a relatively new phenomenon: the default system has always been a gold standard, in which all money is backed by gold — hence ensuring price stability. A gold standard requires that the government or private banks be always ready to redeem bank notes for solid gold, thus limiting their ability to create money from thin air. In other words, under a gold standard, nobody truly controls the money supply, since it is determined by the availability of gold, the value of which everyone can agree upon. This, in turn, prevents prices from fluctuating arbitrarily.

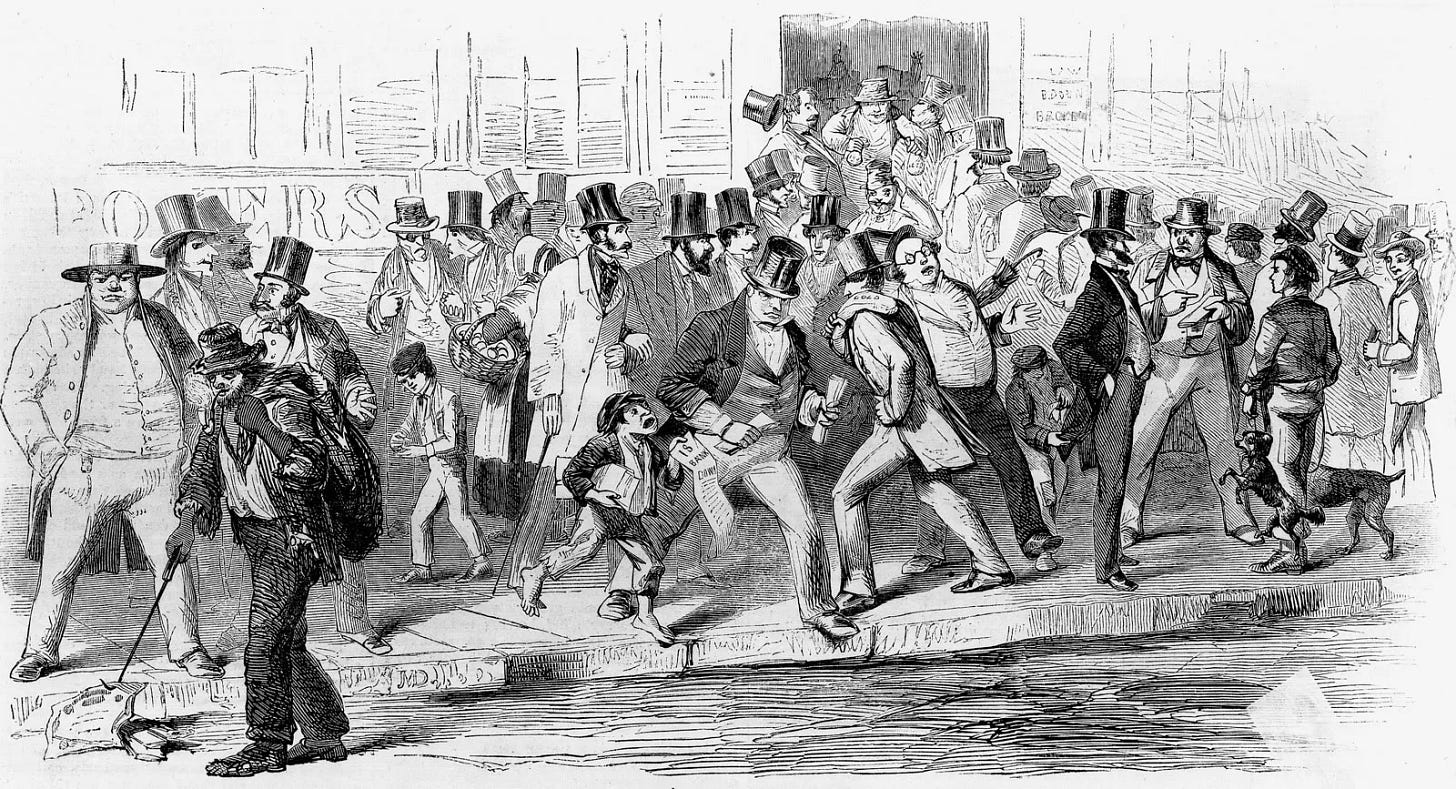

During the late 19th century, the so-called Victorian era, most Western countries had a gold standard, which ensured stable prices. Because prices were stable and inflation was effectively zero, this fostered international trade, and led to an economic boom. Western Europe’s income-per-person grew by 85 percent, and the United States’ per-capita income more than doubled. Of course, there are myriad other factors that go into economic growth, but these data are illustrative. The Victoria era also corresponded with an explosion in science and technology, which some economists attribute in part to the gold standard and the economic prosperity it established.

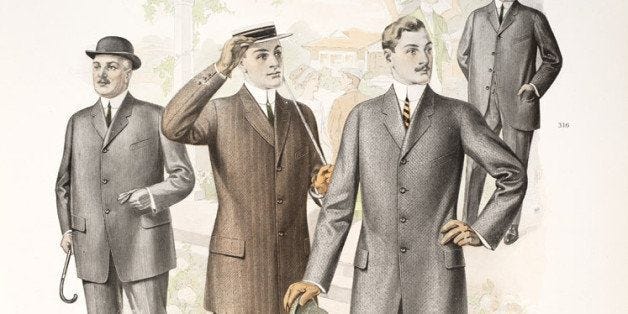

To see how well gold preserves value, consider how much it bought at various points in history. One ounce of gold could buy a finely-tailored tunic in Ancient Rome, and a custom suit in the early 20th Century. Today, you can trade one ounce of gold for around $1,800, which in turn can buy you a bespoke suit. In other words, one ounce of gold can always be traded for the same amount of goods. Over the long run, gold retains its purchasing power, which is one of the reasons people invest in it.

Who controls money?

If I were to ask you who controls money, and you were to respond with, “bankers and the government,” you wouldn’t be wrong. Yet, the way in which they do this, the mechanism of control, is a mystery to most people. As I hinted at the outset, there is likely a reason that those in charge want to keep this mystery under wraps: it is truly diabolical, and should make you pull your hair out. In effect, everything operates through usury: the charging of interest on a loan.

When you go to the bank for a loan, whether it be for a car, house, or something else, then the bank will give you the money, and make you pay an interest rate. For example, if you need $30,000 to purchase a car, and the interest rate is 1%, then the bank will charge you $300 every year, in addition to the $30,000 you have to pay back. Through interest rates, banks make a profit: they borrow money for short periods of time from depositors and other banks, and lend it out to businesses and consumers.

In principle, this means that every dollar a bank lends out should be backed by one it has on reserve, stored in its tills and safes, right? Wrong. When you put your money in the bank, the bank takes your money and, within certain restrictions, can do whatever it likes with it. Usually, this means it lends it out. If you put $100 in the bank, for example, the bank might lend $90 of that out so it can earn interest on it. Banks typically have very low reserve requirements: in Canada, Australia, and the UK, banks are not legally required to keep any money in their reserves.

This is the primary way in which money is created in a fiat currency regime: through banks lending out money. In the example I cited earlier, if you put $100 in your bank account, and the bank lends out $90 of that to a business, then the bank has created $90 in addition to the $100 you deposited. Suppose the business, which received the $90 loan, uses it to pay a worker: the worker in turn deposits the $90 in his bank. This bank, in turn, lends out $80 of the worker’s money, creating an additional $80 in the system. In total, then, $80+$90=$170 of money has been created from the initial $100 deposit. This seems like a confusing conjuring trick, and in effect it is, creating money out of nothing.

Of course, the problem occurs if you want to withdraw your $100. How can the bank return your money if it has already lent it out? Easy. Because the bank has many depositors, it just takes money from its other customers, and gives that to you.

This sounds like theft, and technically it is, but it is completely legal. This process is called fractional-reserve banking.

The real problem is when most depositors want to withdraw their funds — clearly, the bank won’t have enough on reserve to pay back everyone. What is the bank to do in this case? It can call in outstanding loans, or sell off its assets, but if that does not work, then the bank will have to go bust. This is also known as a bank run, and if the panic it causes spreads to other banks, then this can result in a financial crisis.

According to the standard, blue-pilled, and beta account, the Federal Reserve was created to prevent exactly this kind of disaster, by guaranteeing last-ditch loans to banks under distress. I shall show later on why this view is flawed. For now, I’ll just observe that financial crises are not necessarily bad, since they get rid of bad banks with unscrupulous and dodgy lending practices. In general, the discipline that the free market provides is better than that provided by government or centralized authority.

(Furthermore, the gold standard prevented banks from lending out too much, since they had to keep gold in reserves to satisfy customer withdrawals.)

Central banks’ interest-ing story

NOTE: This section is a bit wonkish and technical. If you’re not into the details, then you can skip to the ‘TL;DR’ part.

The Bank of England, established in 1694 and still in existence today, serves as the model for today’s central banks. The Bank, originally a private corporation, held the government’s deposits and was allowed to issue official bank notes and Treasury bonds known as ‘gilts.’ The Bank also sets The Bank Rate, an interest rate which affects the entire economy.

Just like all businesses, banks sometimes have to borrow money. Unlike normal businesses, however, banks use the overnight market, which lets them access one-day loans with incredibly low interest rates. The banks then take the money from these low-interest loans, and lend it out at higher interest, pocketing the difference. This leverage allows the bank to make a profit.

Central banks intervene in the overnight market by either setting interest rates directly, or heavily influencing them. The Federal Reserve, for example, sets the Federal Funds Rate, the interest rate that banks use for overnight loans to other banks. Thus central banks set the interest rate that banks use to lend to each other.

By extension, this affects interest rates throughout the economy, because banks are where people go to get loans. A bank will never charge an interest rate lower than the overnight rate, the one it has to pay one its own loans. Thus, by setting the interest rate at a particular level, a central bank can manipulate the entire economy. When the Federal Funds Rate rises, then mortgage rates go up, and so do interest payments on car loans, business loans, student loans, etc. The central bank, in essence, controls the economy through this simple mechanism.

TL;DR. Central banks, like the Federal Reserve and Bank of England, control interest rates that banks and other financial institutions use to borrow from each other. When the central bank raises these interest rates, then the banks themselves increase the interest rates they charge clients on mortgages, car loans, student loans, etc. This is so they can make a profit from the difference between the interest rates they charge and the interest rates they pay.

Conclusion

If you’ve made it this far without some combination of shock, horror, utter confusion, and possibly anger, then you either know all of this already, or you didn’t properly understand what I wrote. If the latter is the case, then I apologize. Please contact me, or comment below, so I can address your questions.

If you did understand my explanation, then you broadly understand how money, banking, and central banks work. We can now explain how a secret meeting led to the formation of The Federal Reserve [The ‘Fed’] in the United States, and why this institution has caused bank runs, financial crises, and even wars since its birth in 1913. We will also explore its relationship to the gold standard, and how central banking has corrupted the economics profession.