In high school, history was my favourite subject. My teacher was a tall, well-built bald man who looked like Mr. Clean. His lectures were well-organized and captivating.

One day, as we were covering the rise of Adolf Hitler and the National Socialists, Mr. S-- abruptly turned to the class, his brows furrowed, and warned us that racists still exist, and that we should never court their views, or visit online forums like Stormfront. He gestured to the only two Asian students in the classroom, cautioning them to be especially careful.

After school, I sneaked to my parents’ iMac to search up Stormfront, stumbling upon the URL, “stormfront.org.” At the time, I did not understand what I was reading; some of it shocked me, especially since my high school was known to be the most left-wing in the city, and my teachers had successfully indoctrinated me into Left ideology.

However, that fateful visit to Stormfront planted a seed in my mind, which has since sprouted and blossomed. No, I do not subscribe to Nazi ideology, nor do I consider myself a bigot in the conventional sense. Rather, I grew to realize that a lot of history can be reduced to myths, woven to bind society together. These myths contain elements of truth, alongside much fantasy.

One of those myths is that the good guys won World War II: Adolf Hitler, after all, was worse than the devil himself, and The Holocaust of Jews was the darkest woe in history. Had the Allies not defeated The Führer, then our world would mirror Philip K. Dick’s Man In The High Castle, in which Jews and dark-skinned folk are violently persecuted. The Nazis would have overrun America, turning it into a tyrannical landmass in which only ethnic German have rights.

Reddit-tier garbage is what that is. Apologies to Mr. Dick.

More importantly, the World War II myth has let the Left seize power, through the narrative that any serious foe of Leftism is akin to Hitler. Donald Trump, Viktor Orban, and Vladimir Putin have all been compared to the tiny moustache man. We must never allow another Hitler to rise to power, the Left says, lest another world war and genocide manifest.

By this logic, anyone opposing the Left must be a fascist. As a result, actual evil has been allowed to fester unopposed: abortion, euthanasia, castration of children, mass immigration, feminism, homosexuality, “anti-racism,” medical tyranny, and ugly architecture — to name a few. Anyone who threatens this paradigm, even slightly, is crushed; think of Călin Georgescu in Romania, Marine Le Pen in France, or Canada’s Freedom Convoy protesters. In seeking to prevent another Hitler, we have rendered unto ourselves soft totalitarianism.

Therefore, a critical project of The Right is deconstructing the World War II myth. Tucker Carlson has been the most successful in this regard; his interview with historian Darryl Cooper, in which Cooper called British prime minister Winston Churchill “the chief villain of World War II,” was viewed by tens of millions. Candace Owens, whose podcast is one of Spotify’s most popular, has likewise questioned the standard history of Nazi Germany. Granted, this process is painful — being told that Santa Claus is not real always hurts — but it is necessary if we are to mature.

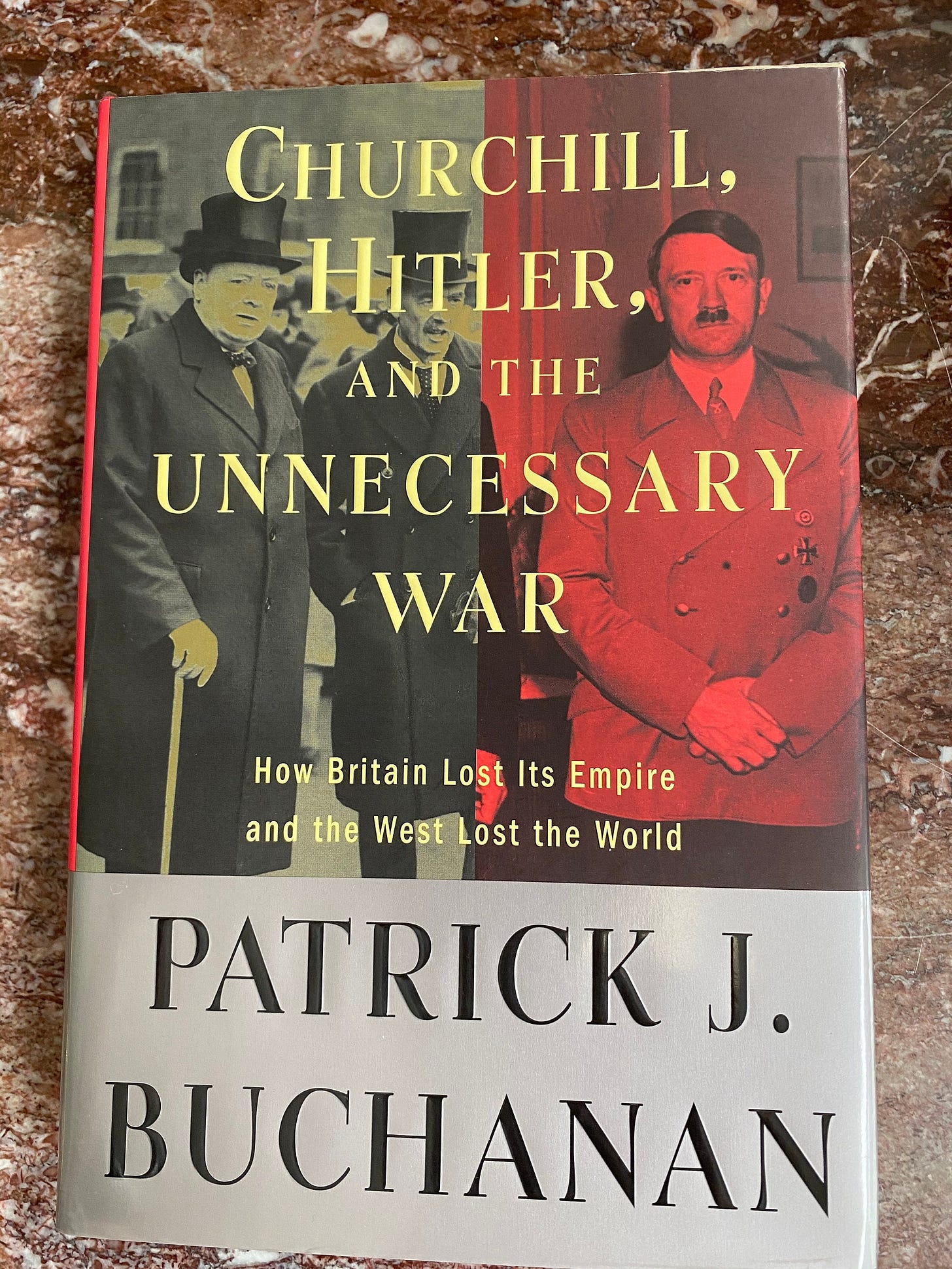

Of course, Tucker and Candace are not the first to tackle this head-on, but they seem to have the advantage of good timing. Prior scholars who tried, and failed, to overturn the idols of WWII include David Irving, Harry Elmer Barnes and Patrick Buchanan. It is to Buchanan’s 2008 book Churchill, Hitler, and the Unnecessary War that I turn to in this review.

If you have a friend who is open-minded and casually interested in history, then get him this book for Christmas. Not only does Buchanan recount the main events leading up to the war in detail, but he has the gift of making history gripping and accessible. He also does not load the reader with too many red pills, which tend to overwhelm rather than inform. Indeed, contrary to what leftist reviews of this book may say, Buchanan relies on conventional history to weave together an alternative tale.

The book’s thesis is simple: Winston Churchill is World War II’s primary villain. The war was useless, destroyed the British empire, and led to the proliferation of communism across the globe. Churchill was a jingoistic bully who pushed to fight the Germans, even at the cost of his countrymen’s lives. Buchanan, an American, suggests that The United States should learn from Britain’s historical debacles, and avoid getting entangled in foreign conflicts with no clear benefit to Americans.

Buchanan opens his tale with the leadup to World War I. At the time, Churchill was First Lord of the Admirality, a position which oversaw The Royal Navy, when it was the world’s largest and most technologically-advanced sea fighting force. In the early 20th century, The United Kingdom signed treaties, joining an informal bloc which included France and Russia, standing against The Triple Alliance of Germany, Austria-Hungary, and Italy. Britain even forged a pact with Japan, so that it could safeguard its colonies in Asia from threats. While the agreement with Japan was wise, the ones with European powers proved disastrous.

As those educated on the topic know, the spark that set war alight was a Serbian nationalist’s 1914 assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, heir to the throne of Austria-Hungary. Austria-Hungary declared war on Serbia, who sought and attained Russian military support. This started a cascade of events, which resulted in Germany, France, Austria-Hungary, and Russia embroiled in war. The continent erupted in flames.

At this point, Britain was not keen to get dragged into war. Its loose alliance with Russia and France was not a binding military commitment. What pushed Britain over the edge, according to Buchanan, was Winston Churchill’s aggressive Cabinet lobbying. The crux of the issue was Belgium, a neutral country which had an 1839 pact with Britain — the pact authorized, but did not require, the UK to protect Belgium in case of hostilities. Hostilities came: Germany plotted to sweep through Belgium and Luxembourg, and then invade France. Buchanan writes,

As [Chancellor] Lloyd George vacillated, Churchill pressed him to take his stand on the issue of Belgium’s neutrality. Churchill knew public opinion would swing around to war when the Germans invaded Belgium, as they must. He believed that Lloyd George would swing with it. Churchill knew his man.

Of course, Churchill himself did not care about Belgium. If war came, he would have also violated that country’s neutrality in order to blockade Germany via Antwerp. Rather, the First Lord wanted war due to strategic concerns should Germany conquer France, but mostly because of his “zest for war,” according to senior bureaucrat Sir Maurice Hankey.

Buchanan cites journalist A.G. Gardiner’s desciption of The First Lord during this time:

He sees himself moving through the smoke of battle — triumphant, terrible, his brow clothed with thunder, his legions looking to him for victory, and not looking in vain. He thinks of Napoleon; he thinks of his great ancestor [John, 1st Duke of Marlborough].

I am not entirely convinced by Buchanan’s depiction of Churchill as a chief instigator of war. World War I was a fool’s errand, no doubt, but the British public were fed propaganda about Germany’s “Rape of Belgium,” and by August 4th, when Germany in fact invaded, most of the British public wanted to fight. Any government that refused to defend Belgium, at that point, would have fallen to a party willing to skewer the Huns. If anything, this speaks to the volatility of the public mood and irresponsible journalism. As Lloyd George observed:

[A poll on August 1st] would have showed 95 per cent against… hostilities… A poll on the following Tuesday [August 4th] would have resulted in a vote of 99 percent in favour.”

Britain would have joined World War I, whether or not Churchill wanted to.

This is a problem that plagues this book: Buchanan overstates Churchill’s role in various historical episodes, and there are too many asides on Churchill’s personality. We learn that he was a drunkard, an atheist, a reckless and selfish brute, a racist, and an occasional anti-Semite. While these are interesting character sketches, they have little to do with the book’s theme. I suppose that, given Churchill’s colossal status in English history, Buchanan felt he had to do some heavy lifting to cast aside the edifice.

Anyway, getting back to the narrative, Buchanan shifts to the interwar years, during which time, Britain ended its naval alliance with Japan, contributing to Japanese aggression in Manchuria and a weakening of British influence abroad. The Germans, after losing WWI, were forced to cede their colonies, pay massive tribute to France, and were subject to restrictions on military rearmament. They also lost a lot of territory in Europe itself.

(As an aside, I was surprised that Churchill, as Chancellor Of The Exchequer, was responsible for The UK’s postwar return to the gold standard at the 1914 rate of £4.25 to the ounce — a decision that led to The Great Depression — yet that is a subject for another article.)

In 1933, Adolf Hitler rose to power in Germany. The Nazis’ goal was to restore German dignity and regain lost German territory in Europe, which had been ceded to Belgium, France, Czechoslovakia, and Poland after World War I. The normie reader might be taken aback at how reasonable Hitler was when it came to geopolitics. For example, recognizing that Benito Mussolini’s fascist Italy was more powerful in 1933 than The Third Reich, Hitler was willing to appease Il Duce by letting him keep South Tyrol, a mostly German-speaking province, in exchange for an alliance. Mussolini scoffed at Hitler, calling him a “plumber in a Mackintosh,” and a “clown.”

Hitler’s main concern was to avoid a two-front war with Russia and Western Europe, while countering communism. In 1938, The Führer reached out to Poland, proposing an anti-communist alliance. The Poles, sworn enemies of the Russians, seemed like natural allies, but in their pride and stupidity spurned Hitler’s overtures. Indeed, the Poles come off poorly in this book, especially in their handling of Danzig, a Polish city that used to be German. Hitler wanted Danzig back, assuring Polish foreign minister Józef Beck that Warsaw could retain economic control of the city, while gaining territorial assurances and land in Slovakia. Beck refused, but a year later, when the British offered Beck an unconditional guarantee of Poland’s sovereignty, Beck accepted. This was folly, as Britain lacked the resources to protect Poland, and the country ended up under the communist yoke for half-a-century.

It was also folly on Britain’s part, since the empire had no strategic interest in Poland, and it would have been in London’s interest for the Nazis and Soviets to fight and weaken each other in eastern Europe. Throughout Hitler’s diplomatic and military jostlings, Winston Churchill was an outspoken backbencher in parliament, decrying the Nazi war machine. Not only did he support Poland’s war guarantee, but he also vociferously opposed Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain’s appeasement of Hitler, as well as the Anschluss and Munich Agreement. Yet both appeasement and confrontation were extremes; as Buchanan argues, what Britain should have done was to ramp up military spending domestically to deter German aggression.

On September 1st, 1939, war came as Hitler invaded Poland. Prior to the invasion, Hitler repeatedly extended olive branches to Britain and France, which were all rebuffed. Instead, Britain and France declared war on Germany on September 3rd. Even well after the war had started, Hitler showed good faith, issuing a “stop order” to his Panzer units so that British troops could escape from Dunkirk in 1940. The Führer sent peace proposals to Britain repeatedly from 1939 to 1940, but the newly-minted Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, refused all of them, realizing he would lose power if he courted peace. Churchill then turned around and engaged the Royal Air Force in a sustained bombing campaign targeting German cities, with the express purpose of destroying civilian infrastructure and morale; 600,000 German civilians perished.

Churchill’s life was devoted to three goals: maintaining the British empire, stopping socialism in its tracks, and preventing war in Europe. He failed in all three of his endeavours. Britain is now a shadow of its former self, overrun by Third World hooligans, and its empire is in tatters. Socialism expanded in Europe after World War II, killing tens of millions and wrecking cultural and religious institutions — even after the Cold War, socialism’s pernicious effects live on in Western culture. War was certainly not prevented; World War II was the bloodiest conflict in history. Churchill was hardly the “Man of the Century” which The Weekly Standard purported him to be.

A minor complaint I have with this book is its lack of maps, which would have helped to clarify what was happening as Hitler rode into Europe, annexing Austria and The Sudetenland, and negotiating with the Poles over Danzig. It would have made clear The Treaty of Locarno, as well as the treaties of Versailles and Saint-Germain-en-Laye. While my familiarity with European geography allowed me to follow the events, maps would have been better.

What can we learn from Churchill, Hitler, and The Unnecessary War, which we can apply to today’s problems? Three things, I think.

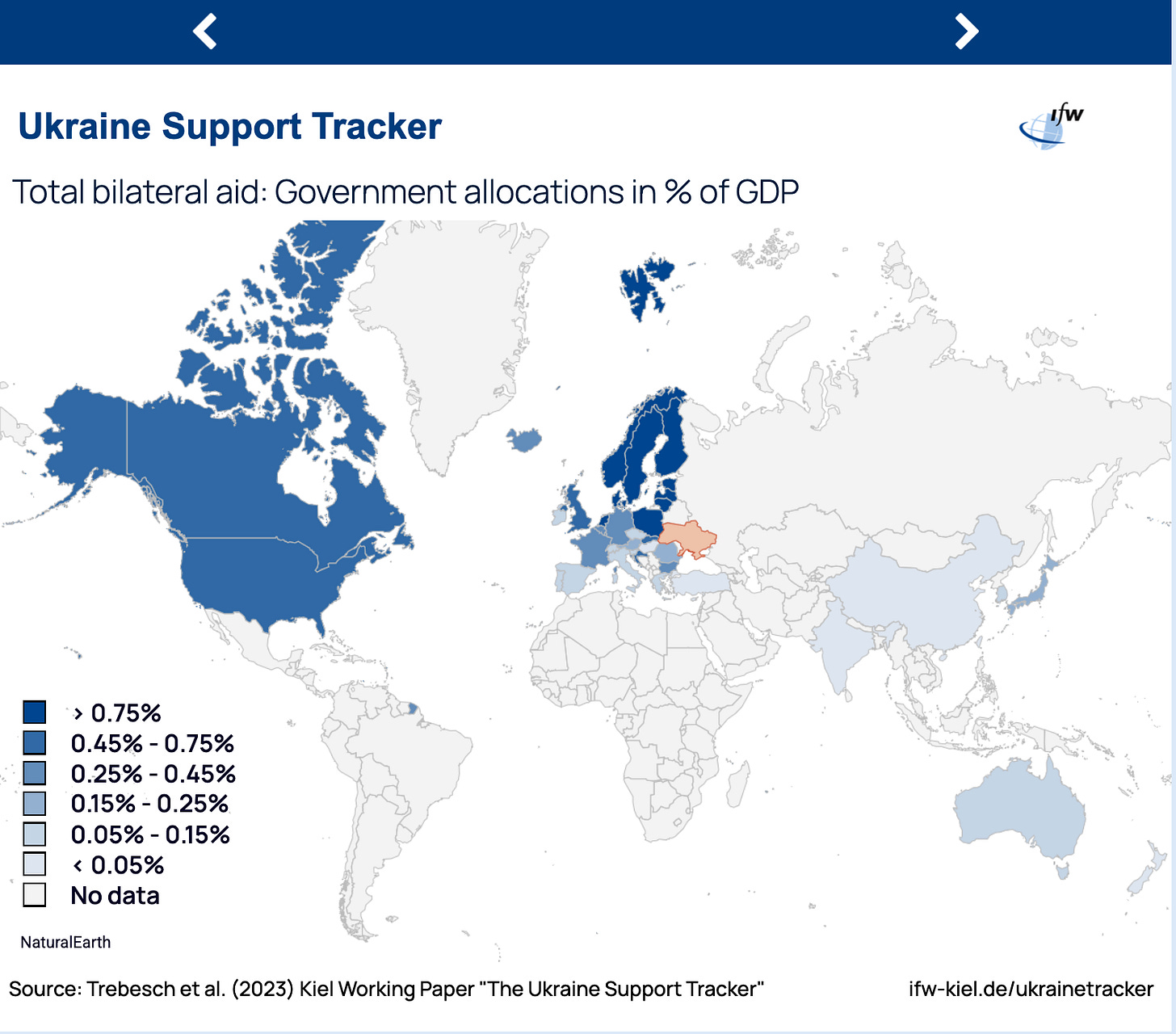

First, although history does not repeat, it rhymes, and confirms George Washington’s sage advice that nations should avoid foreign entanglements. Had the British not given Poland a war guarantee in 1939, or refused to honour it, then the evils of war could have been avoided, and The British Empire would have stood steadfast. Likewise, in our day, had the U.S. and its allies refused to meddle in the Ukraine, then a costly clash with Russia might have been dodged. The Ukrainians might be brave warriors, but that is irrelevant — The West has neither strategic gain nor economic interest in a rump state with a corrupt and backward leadership. Western coin and weapons should not be sent to Kiev, and NATO should instead focus on ramping up its own military production.

Second, the book teaches that history does not move forward through unseen “social and economic forces,” but through the actions of individual men. Hitler was, for all his flaws, a brilliant politician, who peacefully regained German territory which had been stolen after World War I. His actions, combined with those of Churchill, Daladier, Stalin, and others, resulted in World War II. Today, The West lacks such towering figures, and only when such men are allowed to rise again, can history move forward in leaps and bounds. This is evident to those who pay attention, though it defies the gnostic tendency among modern academics to ascribe everything to mystical, sociological phenomena.

Finally, and most importantly, the book shatters a key fallacy, that Churchill was the hero of World War II. It does not suggest, in any way, that Hitler and Mussolini were saints, and even condemns the Nazis for The Holocaust. However, it creates a nuanced picture, which is enough for the normie to sit up and ask questions. The first step towards letting go of delusion is being kicked to the ground to face reality.

Destroying the World War II narrative is crucial if the Right is to advance in its goals. I do not like Hitler, but his reign was successful in many ways. The Nazis destroyed The Leftist stranglehold in Germany. They challenged the Leftist pillars of forced egalitarianism and emancipation from unchosen bonds, hallmarks of Enlightenment thought. Hitler gave the German people unity and purpose, which allowed them to rebuild their economy. The WWII narrative also prevents us from considering other successful right-wing regimes, such as Franco’s Spain or Pinochet’s Chile, and what lessons they may impart to us, as we seek to build a society based on reality.

Perhaps this book will snap your blue-pilled cousin out of his stupor, so that he can help to build society along right-wing lines. At the very least, he will start to ask questions about World War II and Churchill, and that is good enough.

Excellent piece. The Boomer Truth Regime is a horrible one to live under. I also found out that tons of stupid laws came about because of WW1 in England, things that remain like a cancer. Compulsory Purchase, Nationalisation etc. Some people even speculate the 'Yookay' is still being run on a wartime collectivist footing.

One thing that is curious about modern 'thinkers' is they defend the ideology and ignore the results of it. Well, look at the 'Yookay' now - it does not in any way resemble the victor of two world wars. Also, if Churchill was so loved, why was he voted out as soon as possible after the war?

Good article, Churchill was also financed by a conglomeration of Jewish Zionists know as “The Focus”. Churchill was near bankruptcy prior to this group coming to his aid. Hitler was a political risk taker, while being, I would argue, too cautious militarily. His decision not to march on Moscow in the Spring/Summer for 1941 in hindsight might be the biggest military mistake in history.