“My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, it is not either to save or destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave, I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves, I would do it; and if I could do it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that.”

-President Abraham Lincoln, 1862.

The U.S. Civil War (1861-1865) was not about slavery. It was not even about ‘states’ rights,’ as some Southerners might claim.

The Civil War was about economics, just like most wars are. That is it.

Why? How? Let me explain.

To be clear, when I say that the Civil War was not about slavery, I mean that it had nothing to do with moral opposition to slavery. White Americans, in both the North and the South, did not care about the plight of African Americans. However, the institution of slavery itself was a secondary factor and formed the moral justification for the war, which was later concocted to make The Union seem like ‘the good guys.’

Let’s delve into this topic.

This is Part 1 of a two-part series. In this post, I will destroy the myth that the Civil War was about slavery. In next week’s article, I will reveal what the war was truly about.

Please subscribe to stay updated about my latest posts.

A Revealing Map

Just prior to the Civil War, the United States looked like this:

The locations colored in red and pink were part of The United States (‘The Union’), while those states in green formed ‘The Confederacy,’ a group that separated from the United States so that it could control its own economy. Eventually, The Union and The Confederacy went to war against each other.

If you look closely at this map, then any notion that The Civil War was about slavery is dispelled; there were slave-holding states that were part of The Union. These states — Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri — permitted slavery, but still fought against the Confederacy, where slavery was also lawful. Already, the claim that slavery was a cause of the war seems shaky.

Corwin Crushes The Myth

Before The Civil War, the U.S. had 19 so-called ‘free states,’ in which slavery was outlawed, and 15 ‘slave states’ in which it was legal. The free states were typically in the North, and included New York, Illinois, and Michigan. The problem, for those who claim that the Civil War was about the abolition of slavery, is to explain why many free states supported the Corwin Amendment.

The Corwin Amendment was a proposed change to the U.S. Constitution which would have prevented the federal government from interfering in slavery. In February of 1861, Rep. Thomas Corwin from Ohio submitted his version of the amendment to the House of Representatives, where it passed 133-65. It later passed in the Senate by 24 ‘yea’ to 12 ‘nay’ votes. President Abraham Lincoln did not oppose its implementation, and sent it for ratification to the state legislatures.

The Corwin Amendment, if were passed, would have preserved slavery in the U.S. Before the amendment could be fully ratified, however, the U.S. Civil War started. On April 12, 1861, the first shots were fired.

Several Congressmen from free states supported the Corwin Amendment, including Corwin himself. Senators and representatives from the free states of Rhode Island, Illinois, Ohio, Connecticut, California, New Jersey, Iowa, Pennsylvania, Minnesota, Massachusetts, Wisconsin, and Vermont voted in favour of the amendment. Again, the claim that the Civil War was about slavery falls apart.

Abolitionists Were A Fringe Minority

The population of the Union, on the eve of the Civil War, was 22.7 million: 19.2 million in free states, and 3.5 million in Union slave states. According to the American Abolitionists website, there were 255,000 abolitionists and anti-slavery activists just prior to the Civil War. In other words, 1.1% of the Union supported the cause of abolition, a small minority.

By way of comparison, consider the Libertarian Party in the 2020 U.S. Presidential Election. In 2020, its presidential candidate Jo Jorgensen received only 1.2% of the vote. From this, we can surmise that abolitionism in the Union, just prior to the war, was about as popular as the Libertarian Party is today.

To be sure, many northerners would have supported abolition in principle, but not to the point of going to war over it, or even provoking their southern white countrymen.

A good demonstration of this is the advent of The Liberty Party, a U.S. political party which lasted from 1840 to 1860. The party was devoted to ending slavery, but was never successful politically. At its peak, it recevied only 2.3% of the popular vote.

The Republican Party at the time had an anti-slavery faction, but these members were so extreme that they were called ‘The Radical Republicans.’ Prominent members of this faction included Pennsylvania representative Thaddeus Stevens, whose anti-slavery views lost him so much support that he did not seek re-election in 1852. Abraham Lincoln, himself a Republican, never joined the Radical wing in his party.

Another Radical Republican, senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts, was nearly beaten to death — on the Senate floor — by South Carolina congressman Preston Brooks, who was offended by Sumner’s anti-slavery speech. To be fair, Sumner used the occasion to also attack Brooks’s first cousin. The other congress-men, including Republican members, did not intervene while Brooks was caning Sumner within an inch of his life.

A concerted effort by U.S. public schools has extolled the virtues of anti-slavery campaigners like Frederick Douglass and Harriet Beecher Stowe, to make it appear as though these radicals were the reason for The Civil War. Although these individuals had their merits, their views were fringe.

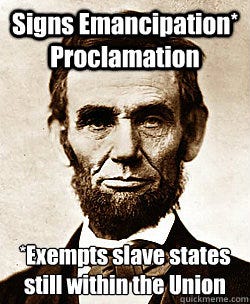

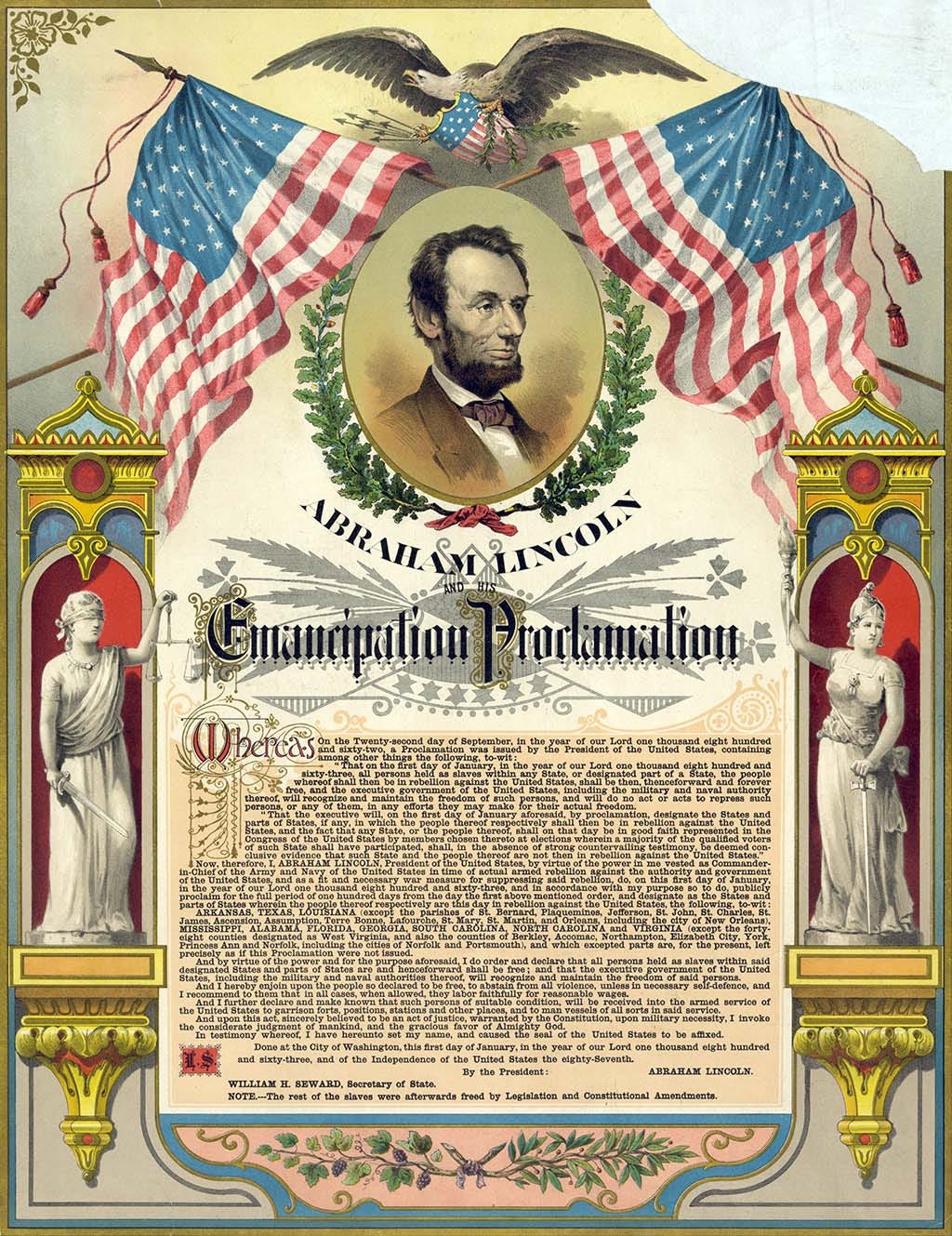

Muh Emancipation Proclamation

In 1863, President Abraham Lincoln signed The Emancipation Proclamation, which freed the slaves — kind of. Slavery was allowed to continue in those Union states — Delaware, Kentucky, Maryland, and Missouri — which still had slaves. Slavery was only abolished in The Confederate States.

Writing in The American Heritage Pictorial History of the Civil War, Bruce Catton explains,

Technically, the proclamation was almost absurd. It proclaimed freedom for all slaves in precisely those areas where the United States could not make its authority effective, and allowed slavery to continue in slave states which remained under Federal control… But in the end it changed the whole character of the war and, more than any other single thing, doomed the Confederacy to defeat.

The Emancipation Proclamation was a tactical move. It transformed an unpopular war, known in the North as a “Rich-man’s war,” into an antislavery crusade, providing a moral justification for the conflict. It also caused chaos in the Confederacy, where slaves struggled to flee north and join the Union Army. White soldiers now fought with the false sense that they were fighting a godly war.

As Lincoln himself wrote in a letter, just prior to implementing emancipation,

Things had gone from bad to worse until I felt we had reached the end of our rope on the plan we were pursuing; that we had about played our last card, and must change our tactics or lose the game. I now determined upon the adoption of the emancipation policy.

I am not sure how to make it any clearer.

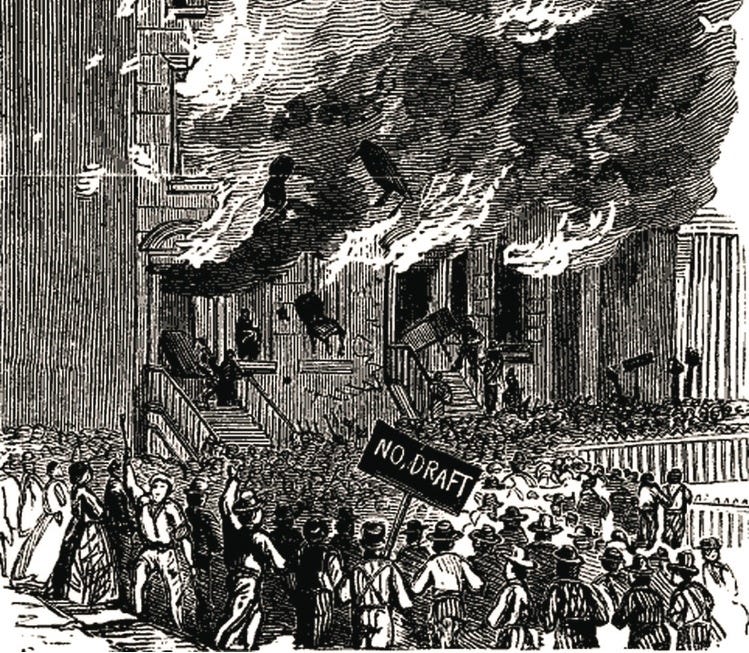

Draft Riots and Dodgers

A test of whether a nation truly supports a war is to see how its men respond to being forced to fight in it. In World War I and World War II, there was no significant opposition to conscription, since U.S. propaganda had convinced Americans that fighting the Germans was a noble endeavor. When President Lincoln enacted a draft during the U.S. Civil War, however, the reaction was one of outrage.

In 1863, the U.S. Congress passed the Enrollment Act, ordering fighting-age men to either enrol in the armed forces, or pay a $300 fine. Wealthier men chose to pay the fine, while working-class Americans had to join the military. Opposition to conscription erupted throughout the Union, especially among the white working classes and poor.

A prominent example is the New York City draft riots, in which armed mobs clashed with police and Union army forces, in an outburst of anger toward the draft. The (mostly) Irish rioters destroyed abolitionist offices, ransacked black homes, and burned down an African American orphanage. Once the army quelled the riots, 120 people had died, and over 2,000 were wounded.

Riots against the draft also occurred in other cities, like Detroit and Boston.

Even if they did not riot, most Union men successfully dodged the draft, whether through legal or illegal means. Of the 776,829 men called to join the military, only 46,347 became soldiers. In percentage terms, only 6% of those who were conscripted showed up for active service. Draft dodging, in its tacit manner, shows that there was widespread opposition to the Civil War.

Again, we have clear evidence that white Northerners were not abolitionist enough to bleed for black slaves.

Conclusion

If you have read this article in its entirety and understood it, then it is obvious that the Civil War was not about slavery.

I will add one more piece of data: the vast majority of Confederate Army soldiers did not own slaves.

So, what were they fighting for? What was this truly about? That will be the subject of my next post.

Stay tuned, and subscribe to stay up-to-date on my latest Substack articles.

I've always liked a kind of Marxist approach, how the industrial middle classes of the North clashed with the land owning aristocracy of the South. Slavery was a wedge issue, but in reality it was the balance of power tilting geographically, economically and culturally which even put the slavery issue on the table.