It is a foregone conclusion, among many conservatives, that Britain is a lost cause: its empire gone, its heroes slandered, and its morals crumbling as foreigners scour the land in search of young English maids to ravage. Within the past year, while ignoring the black and brown invaders pillaging their country, the UK parliament surrendered to The Death Cult, legalizing euthanasia and removing all barriers to abortion. Their once glorious capital, London, is now ruled by a Pakistani Muslim who hates native Britons. There appears to be no hope for old Albion.

This grieves me deeply, as I once dwelt in England for many years and know its character. The Brits are a brilliant people, having conquered one-quarter of the globe, and having subdued the heights of science, literature, and engineering. English parliamentary democracy, and the ideas it spawned, have shaped the world. Furthermore — and this is objectively true — British cuisine is the finest in the world, to the point that the Indians even stole culinary ideas from their English colonial overlords.

In other words, the British were and are unusually talented, and yet they have squandered their talents chasing after dead ends.

There are few better examples of this, in modern times, than the film 28 Years Later, which I have just finished watching so that you do not have to.

Yes, it was that bad.

The Demons Within

A sequel to 28 Days Later and 28 Weeks Later, this film is, at first glance, a zombie horror flick. In fact, 28 Years Later is a standalone motion picture, and the zombies are merely the proximate cause of societal collapse — they are a threat that reveal something deeper. The director, Danny Boyle of Slumdog Millionaire fame, uses this movie to make a point about Britain specifically: the country is clearly heading towards ruin, and there is nothing to be done about it.

In other words, just give up and find your own path in life. A crisis will come, and whether that crisis is a zombie apocalypse or nuclear war, England is too weak to successfully overcome it. Essentially, Boyle puts forth a nihilistic creed. He is especially keen to point out that Christianity is of no use. Boyle would not only agree with Nietzsche’s maxim, that “God is dead,” but would go further: “God is dead, The Church is dead, nothing really matters, and that makes me happy.”

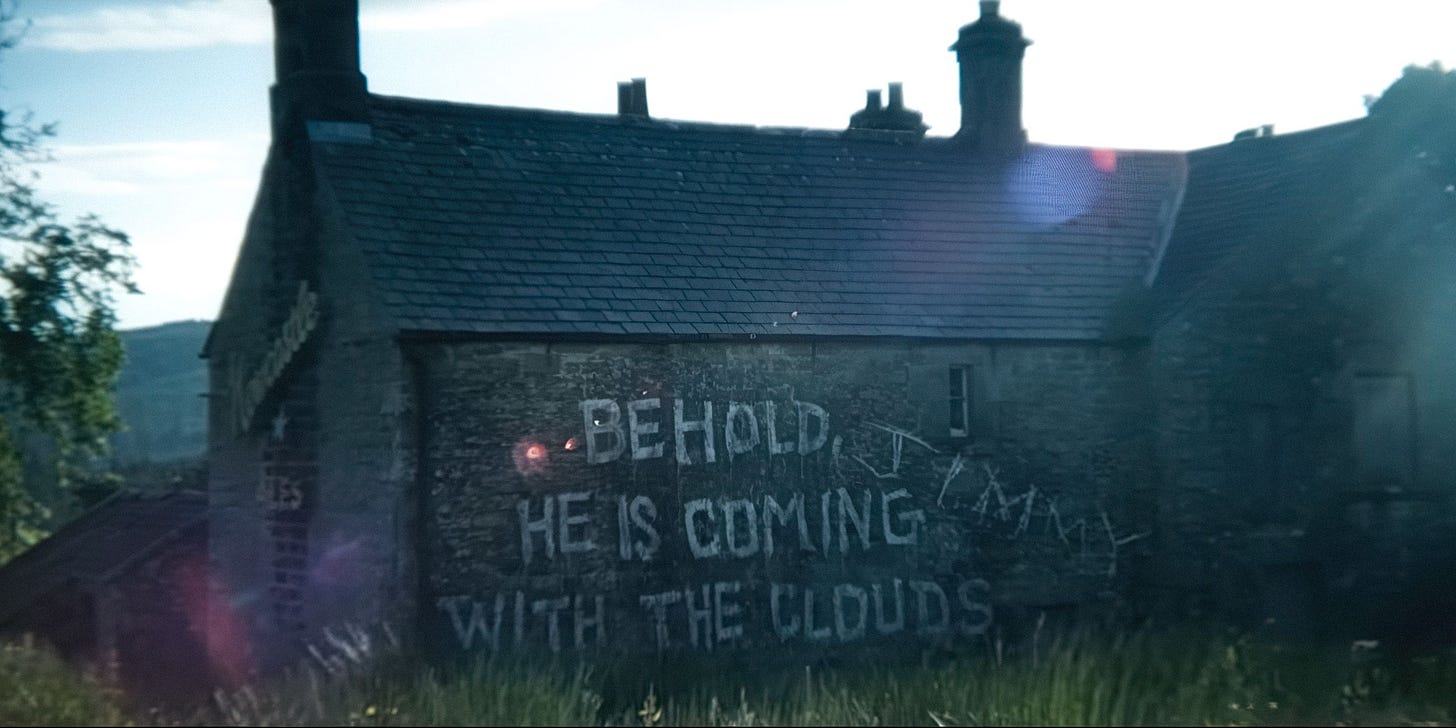

This is a profoundly anti-Christian work, from the very first scene to the last frame. The tale begins in 2002 with a young lad, Jimmy, fleeing from zombies who are chasing him through the Scottish highlands. He stumbles into a church, where his father, the local vicar, is kneeling in fervent prayer. Jimmy begs his dad to protect him, but the vicar wheels about, eyes ablaze with madness, proclaiming that “The Day of Judgment” is at hand. He thrusts a silver crucifix into Jimmy’s hands, and then cackles as zombies force their way into the church and bite him, turning the priest into a snarling, infected wretch. Jimmy manages to escape, the crucifix in his fingers. We do not encounter him again until the film’s final scene.

Twenty-eight years later, we discover that The Rage Virus, which turns healthy men into rabid zombies, has been eradicated across continental Europe but lingers in The British Isles, which have been designated a quarantine zone.

Amid this chaos, an isolated village in Lindisfarne, a tidal island off of England’s northeast coast, remains healthy and steadfast. Although the film does not mention it explicitly, Lindisfarne was historically an important centre of medieval Christianity until the Vikings sacked and burnt the island’s monastery. This is not accidental: the movie identifies Lindisfarne with a kind of salvation, albeit a fake one.

The story shifts to Spike, a 12-year-old boy on Lindisfarne, who is bracing for his rite of passage: a perilous journey to the mainland to hunt for zombies. We soon learn that his mother, Isla, is ill and bedridden, suffering from delusions and migraines. Spike’s father, Jamie, prepares breakfast: a simple cross on the kitchen mantle offers a hint of faith, though no other signs suggest the family is particularly devout.

Jamie and Spike, father and son, set off for the mainland, after being warned that should they fail to return, then they’re on their own. With their bows and arrows in hand, they hike into the thick wilderness of Northumberland as Rudyard Kipling’s “Boots” plays in the background: a poem about soldiers going mad from endless and monotonous marching. As Kipling’s verse is read, clips of English troops fighting in various wars, from the Hundred Years’ War to World War II, are played, conjuring up a time when Britain was truly glorious. The contrast with the movie’s primitive setting is stark.

The two adventurers kill a few zombies, leading to hair-raising scenes. They chance upon a zombie that has been strung up, upside down in the air, and is barely alive. Jamie tells Spike to kill the creature, since it is no longer human, having lost its mind and hence its soul. Spike hesitates, and only launches his arrow once the monster breaks loose from its bonds with its final ounce of strength. Having successfully neutralized the threat, Spike and his father hurry back to Lindisfarne, chased by infected beings.

At the celebration which follows, Jamie exaggerates his son’s exploits, embellishing the story of how they escaped from a zombie hoard. Spike then catches his father carousing with the village’s school teacher, Rosie, who was earlier seen teaching pupils the lyrics to “Abide With Me,” an Anglican hymn. Hypocrisy abounds: Christianity is merely a nostalgic ruse, a rusty rampart holding society together. The men of Lindisfarne, such as Jamie, are weak; they are cheaters and liars.

Jamie lies about one particularly important detail; he refuses to tell his son that on the mainland lives Dr. Ian Kelson, a former general practitioner, who might be able to heal Spike’s mother, Isla, from her illness. When Spike finds out about this, he sets off for the mainland with his mom, leaving his dad behind — after setting fire to a building, as a decoy. We see the English flag, the herald of St. George, catch fire as mother and son set off on their journey. Lindisfarne, the symbol of British Christendom, only offers the illusion of civilization. To find healing, Spike and Isla must escape the island.

After various twists and turns, Spike and his mother reach Dr. Kelson, who leads them to his abode: a graveyard of skulls, piled on high like a pyramid. When asked about this grim display, the doctor explains to Spike that this is a memento mori, a remembrance of death. Yet, Kelson — who treats both healthy men and zombies as equals — does not explain precisely why we should remember death, except for hinting that life is short and shallow. He does not espouse religion. This is clearly nihilistic: like the pyramid of skulls, the cycles of birth, life, and death are meaningless.

To be fair, it is possible to read an existential argument into this tale — without ruining much, Spike symbolically climbs Sisyphus’s hill, the skull pyramid, to complete his journey into manhood and meaning. However, I am not convinced. Dr. Kelson, the man of science, offers only materialist solutions, including euthanasia. His memento mori implies that survival alone matters, as long as it does not come with excessive pain.

This is an inversion of the original meaning of memento mori, the Christian idea that one must live a godly life, since we all die and will be judged by God. In the Christian understanding, pain and suffering can be spiritually beneficial, since they cleanse us from sin and impel us to return to Christ.

In the film’s final moments, Spike abandons Lindisfarne so that he can forage, by himself, on the mainland. A zombie pack chases him, whereupon he is saved by Jimmy, the Scottish boy from the opening scene, who has now become a man. This grown-up Jimmy, with his track suit, long frizzled hair, and golden tooth fillings, eerily resembles the real-life Jimmy Saville, the BBC children’s presenter and sexual pervert, whose crimes included raping children as young as five. The fictional Jimmy retains his father’s crucifix, which he wears on his neck — upside down. He leads a pack of “Jimmies,” who comb Britain seeking zombies to kill, and invites Spike to join his band of oddballs.

And there the movie ends, just as it started: insulting Christianity.

The Altar of Nothing

Britain’s ancient Christianity, which reached its peak on Lindisfarne in the 7th and 8th centuries, cannot save the nation, says Danny Boyle, the director of 28 Years Later, who makes it abundantly clear that Christianity is a mere crutch which lacks the raw manliness required to withstand a crisis. Forget St. Alfred The Great, the Wessex king who pushed back the Viking invasions. The national churches of England and Scotland are faint shadows of their former selves, and a return to Christianity will condemn the British Isles to The Dark Ages.

I partly agree: the national churches are weak. The Church of England blesses homosexuals, ordains women, and permits abortion. The Church of Scotland is worse, allowing gay weddings and Quran readings as part of its divine services. The Church of Ireland is not much better. All three churches push for untrammelled immigration, supporting the invaders with food and shelter. Boyle, who grew up Roman Catholic, likely knows that his own faith tradition is likewise far gone.

“What happens if our culture dies?,” Boyle posed to Rolling Stone in an interview about this film. The culture is already dead, in a way: the film depicts this in the person of Jimmy, whose pious upbringing results in him turning into a caricature of a violent pedophile. There is something of The Marquis de Sade in this: if we abandon God, then all that remains is power and pleasure, both of which must be optimized while we are alive — even if that means engaging in the darkest delights.

Boyle resists calling 28 Years Later a zombie flick, insisting that it is, rather, about societal collapse. He is correct: the zombies are merely a device to put bums in cinema seats. This movie is about the state of the British people, made clear by the fact that all of the film’s characters are white. At first, this is refreshing, until one realizes that Boyle is really mocking white Britons, who have nothing to cling on to; there is no happy ending for them, as they have lost their soul, becoming spiritually infected.

However, contrary to Boyle’s dim view, this is not a foregone conclusion. There is hope. The solution is for Brits to return to the faith of their ancestors, such as St. Alfred The Great and St. Cuthbert of Lindisfarne: that is, Orthodox Christianity, which has never compromised on its doctrines. The Orthodox Church in the UK is experiencing a dramatic surge in converts, especially among the young, which bodes well for the future of the kingdom. Without a strong return to Christ, Britain is doomed to spiritual paralysis, and will be unable to resist the coming troubles.

To be sure, 28 Years Later is technically well-made, though I have minor quibbles. The jarring use of red lighting and excessive gore were irritating. There is a side plot in which a team of Swedish soldiers, armed with AR-15 semi-automic rifles, are unable to defeat a small group of unarmed walking dead, who quickly overwhelm them. After witnessing such an unrealistic, stupid scene, I would not be surprised to find out that the filmmakers are anti-gun zealots. Boyle, based on his public statements, appears to be a Leftist.

Yet none of these are fatal errors per se. Rather, the film’s nihilistic tone makes it almost a parody of itself; if nothing matters, then why not just commit suicide and be done with the hellish, zombie-ridden landscape? There must be something to live for, aside from existential angst or sadistic pleasures. Only when the Brits confront their spiritual malaise, will they again rise to their true level of greatness. Mounting an anti-Christian crusade is useless at best, and at worst, will lead to utter ruin.

A sequel to this film is coming out in January, 28 Years Later: The Bone Temple. Given that I have already wasted two hours on this movie, I do not intend to watch its successor. Instead, perhaps I will read a book about the heights of British achievement: about men like Shakespeare, Newton, and Nelson. Better still, perhaps I will embark on a pilgrimage to Lindisfarne, where the spirit of British Christendom was first awakened… and is awaiting to be rekindled.