How to Prevent a Coup

The Economics of Coup d'États

The coup attempt in Russia has failed. Coup leader Yevgeny Prigozhin has fled to Belarus, and Prigozhin’s Wagner army has been largely disbanded. Russian president Vladimir Putin remains in power. Everything is as it should be.

I will not analyze the past weekend’s events in this article. That has already been admirably done here. Whether this is an ongoing psy-op is of no interest to me.

Instead, I discuss coups more broadly. I submit that three conditions must be satisfied for a successful coup:

The military is unhappy with its pay and benefits.

Powerful factions abandon the political leader.

Ethnic or religious tensions spill over into conflict.

A successful leader therefore pays his soldiers well, maintains strong allies who support him, and channels grievances into peaceful politics.

Putin has succeeded in these things, and for now, is immune to a coup. That might change in the future, but I never suspected he was in danger in this latest debacle. Even before Prigozhin turned his head in shame, I tweeted this:

If you enjoy my content, please subscribe. If you want to support me, then consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Rule 1: Pay Your Military Well

Leaders who pay their soldiers poorly are inviting a coup. This is fairly obvious: an army marches on its stomach. If troops are not paid and they struggle to eat, then they are more likely to overthrow the leader.

This is the experience of history, including in Ancient Rome. The Roman Empire is an ideal setting to observe this: it lasted for over four centuries, and saw 82 emperors take power. Nearly twenty percent of these emperors were assassinated. One study finds that years of low rainfall meant more assassinations.

The reason is straightforward: less rainfall means less food. Roman troops stationed in Germania (present-day Germany), for example, had to grow their own food. They could not rely on shipments of grain from Britain or Italy. In 69 AD, bad weather caused Batavian troops in Germania to revolt, due to lack of food and pay. This led to the emperor Vitellius’s assassination that same year — at the hands of German soldiers.

Good leaders therefore pay their soldiers well, and ensure they’re well-fed.

However, what happens if a rich man co-opts the military, offering to pay soldiers even more if they kill the leader?

Rule 2: Manage Your Allies

In every country, powerful groups compete to rule. A successful ruler manages these elites, and if they pose a threat, he builds new alliances.

Modern-day Russia is a good example of this. Vladimir Putin has built coalitions with oligarchs in different industries. This reduces risk: if manufacturing titans revolt, then Putin can still rely on support from businessmen in the transport, mining, and media sectors. Prigozhin’s recent coup attempt failed largely because other Russian oligarchs did not support it.

On the other hand, too small of a coalition can threaten a ruler’s survival. Julius Caesar, for example, crossed the Rubicon in 49 BC and declared himself Dictator of Rome. Although he was popular with the people, his support among the elite was limited to a few men like Mark Antony. The Senate hated Caesar, viewing him as insolent and tyrannical.

In 44 BC, a group of sixty senators lured Caesar to the Theatre of Pompey and stabbed him to death. Caesar’s lack of broad-based elite support was his undoing. His support among the masses meant nothing.

Rule 3: Quell Ethnic and Religious Tensions

Religious and ethnic tensions can lead to fractured coalitions. Rulers who fail to quell these tensions can face removal.

This is best seen in post-independence India, a country with over 700 ethnic groups, 22 official languages, and more than 10 religions. When Indian rulers fail to pacify unrest between groups, chaos ensues and politicians can even be killed.

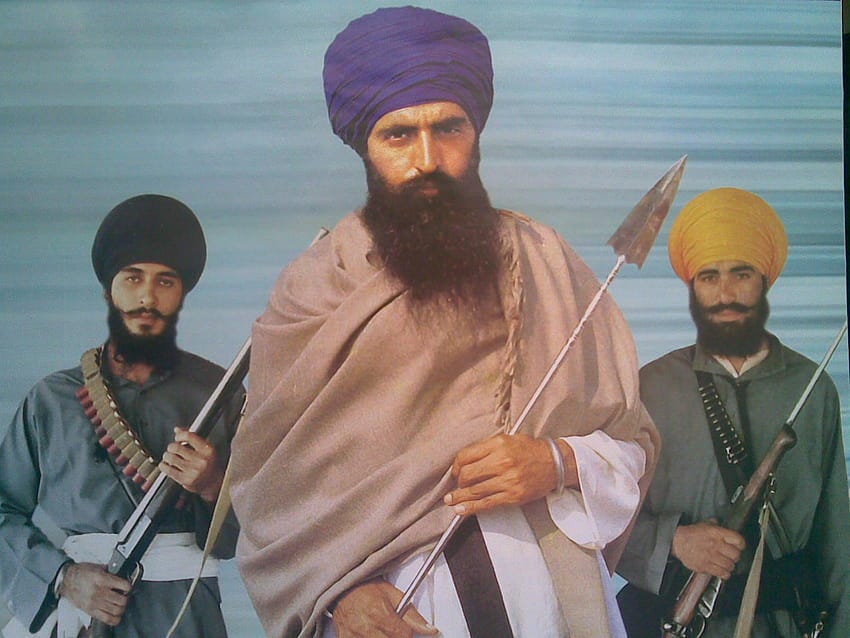

This happened to Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, who suppressed a Sikh uprising in the 1980s. In 1983, Sikh militant Jarnail Singh Bhindranwale (pictured above) took refuge in The Golden Temple, the holiest site in Sikhism. Campaigning for an autonomous Sikh state within India, Bhindranwale used violence effectively. He encouraged Sikhs to buy guns and motorcycles, anticipating a showdown with the Indian government.

The showdown came in 1984. On June 1st of that year, the Indian army occupied The Golden Temple, and massacred over 700 Sikhs, including women and children. Bhindranwale was killed. On June 10th, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi ended the military operation, having triumphed over the Sikh nationalists.

However, Gandhi ultimately failed in the game of power. Her own Sikh bodyguards murdered her on October 31st, 1984. Gandhi had overstretched, and failed to heal wounds with Sikhs in India.

Conclusion

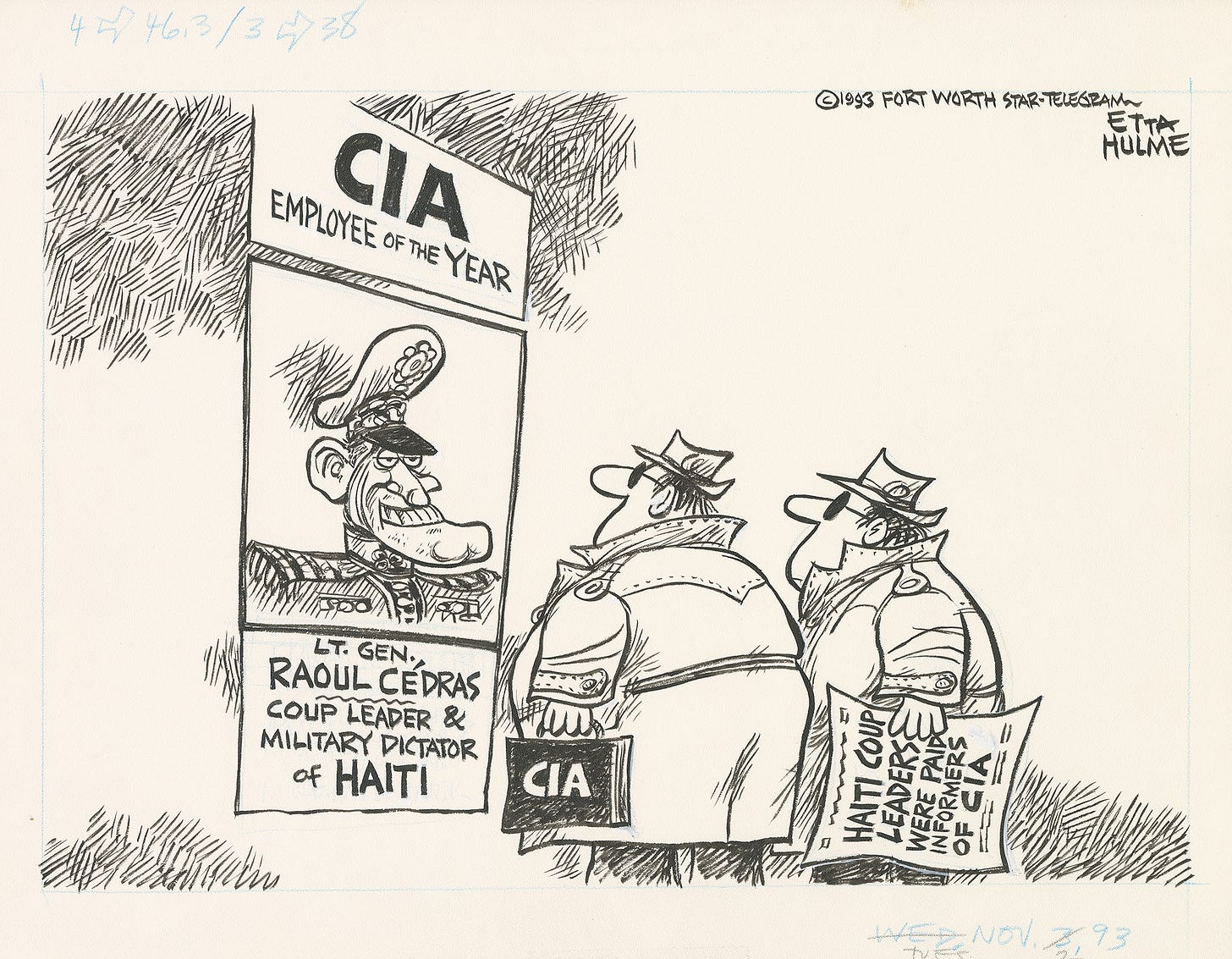

Since World War II, most coups have been CIA-sponsored. I would not be surprised if that were the case with the recent Prigozhin attempt. By bribing the military and elite, and stoking ethnic tensions, the CIA has successfully staged coups in various countries, from Ukraine to Guatemala.

The rules of preventing coups can be reduced to a single concept: keep the important people satisfied. Russia is again a good case study. It pays its soldiers 10 times the average wage. Putin, as I mentioned, maintains good relations with oligarchs. And Russia manages ethnic and religious conflict well.

(There is rarely violence between Russian ethnic groups, although there are 120 of them. During the Ukraine conflict, the various ethnicities banded together against Zelensky’s forces. Chechens liberated Mariupol, while Cossacks defended Crimea. There is a sense of Russian identity which unites people.)

In summary, the economics detailed here can predict successful coups — even if you know little about the country in question. Country expertise is important, but game theory applies everywhere. Competent leaders, including Putin, Erdogan, and Netanyahu, thwart coup attempts, keeping their nations stable. There is much to learn in studying their examples.

Note to self: Become a world leader, pay soldiers handsomely, befriend all the oligarchs